Feb 18

/

James Kavanagh

Demonstrably Safe: The Waymo Way of Adaptive Governance

Most writing about AI governance begins with failure. This article begins with the most impressive safety record of any autonomous system, and asks what approach to governance makes it possible.

I started writing the Doing AI Governance newsletter a year ago to share what I've learned about governing intelligent systems. Four months ago I launched the AI Governance Practitioner Program to teach the real-world practices of AI Governance. As I spoke with and taught more practitioners and fielded more questions, I realised I needed to step back and name the foundations of my own approach. I've been practising adaptive governance for most of my career, across process safety, cybersecurity, cloud infrastructure, and AI. I didn't always call it that - it was simply how I did the work and led my teams. The thinking of Leveson, Dekker, Hollnagel, Rasmussen, Weick has shaped how I work for decades. Heifetz and Edmondson changed how I think about leadership and culture. But it was always instinct refined by experience and the application of theory rather than something I could package and hand to someone else. This article is the result of six weeks of reflection making that explicit, and it's the first of many articles I'm writing on how adaptive governance really works.

In AI governance, if we're not poring over regulatory interpretations, we spend much of our time studying what went wrong, or identifying what could go wrong. Biased hiring algorithms. Autonomous vehicles that dragged pedestrians while the company lied to regulators. Facial recognition deployed without adequate legal safeguards. Emergence of dangerous behaviours in previously 'safe' systems. These are important stories and I've written about and you'll find many of them in this blog. But a steady diet of failure cases can leave you with the impression that governing AI well is about avoiding catastrophe, that the best you can hope for is to not make the news. Or worse, achieve little more than compliance with minimum legal baselines.

I don't think that's right. I believe meaningful, effective governance that accelerates safe innovation is very achievable. It requires a different mindset and approach. But I've been a part of that, and I've witnessed such approaches creating meaningful, sustained governance in practice.

So I'm going to start somewhere different today, with success rather than failure.

I want to start with Waymo. Because what they've built isn't just an impressive feat of engineering and regulatory engagement. It's one of the clearest examples I've seen of what governance looks like when it's designed into a system from the ground up, and the safety data and governance practices emerging from it deserve serious attention. If you work in AI Governance, you owe it to yourself to learn the Waymo way.

Over 100 Million Miles of Evidence

Waymo's autonomous vehicles have now driven well over 100 million fully autonomous miles on public roads, with no safety driver and no human behind the wheel. Just the AI system, navigating real traffic, real pedestrians, real weather, real edge cases.

The safety record across those miles is worth examining closely. Waymo's own data, published through their Safety Impact Hub and verified against NHTSA reporting, shows a more than tenfold reduction in crashes involving serious injuries compared to human drivers. Through September 2025, across 127 million rider-only miles, the numbers hold up to scrutiny in ways that most AI safety claims can't.

And these aren't just Waymo's assertions about its own performance. The safety case is backed by a growing body of peer-reviewed research. Kusano et al. published a crash comparison at 7.1 million miles in Traffic Injury Prevention in 2024. Di Lillo et al., in a collaboration between Swiss Re and Waymo developed a rigorous safety comparison methodology and found statistically significant safety advantages. A further Swiss Re study at 25.3 million miles, comparing Waymo's third-party liability insurance claims against human benchmarks, found an 86% reduction in property damage claims and a 90% reduction in bodily injury claims.

The most recent peer-reviewed study, published in Traffic Injury Prevention in 2025, extends the analysis to 56.7 million miles and breaks it down by crash type. The findings show a 92% reduction in pedestrian injury crashes and a 96% reduction in intersection injury crashes. Those aren't marginal improvements. That's a whole different category of safety performance.

Seat belts cut fatal risk ~45%; helmets cut serious head injury ~60%; child restraints cut infant fatalities ~71%; life jackets cut boating deaths ~80%. Quantified risk reduction in safety of >90% is staggering, almost unprecedented.

Now you could read those numbers as a story about better algorithms and better sensors or the elimination of human error. The engineering is world-class. But if you look closer, I think the numbers are telling us something much deeper about governance, and what it takes to embed governance into the design, development and operation of intelligent systems.

You can watch and listen to an expanded version of this article in a FREE course of the AI Governance Practitioner Program

Demonstrably Safe AI

Waymo describes their approach as "Demonstrably safe AI. Safety that is proven, not just promised". Nice tagline, but they genuinely back it up with real architecture and evidence.

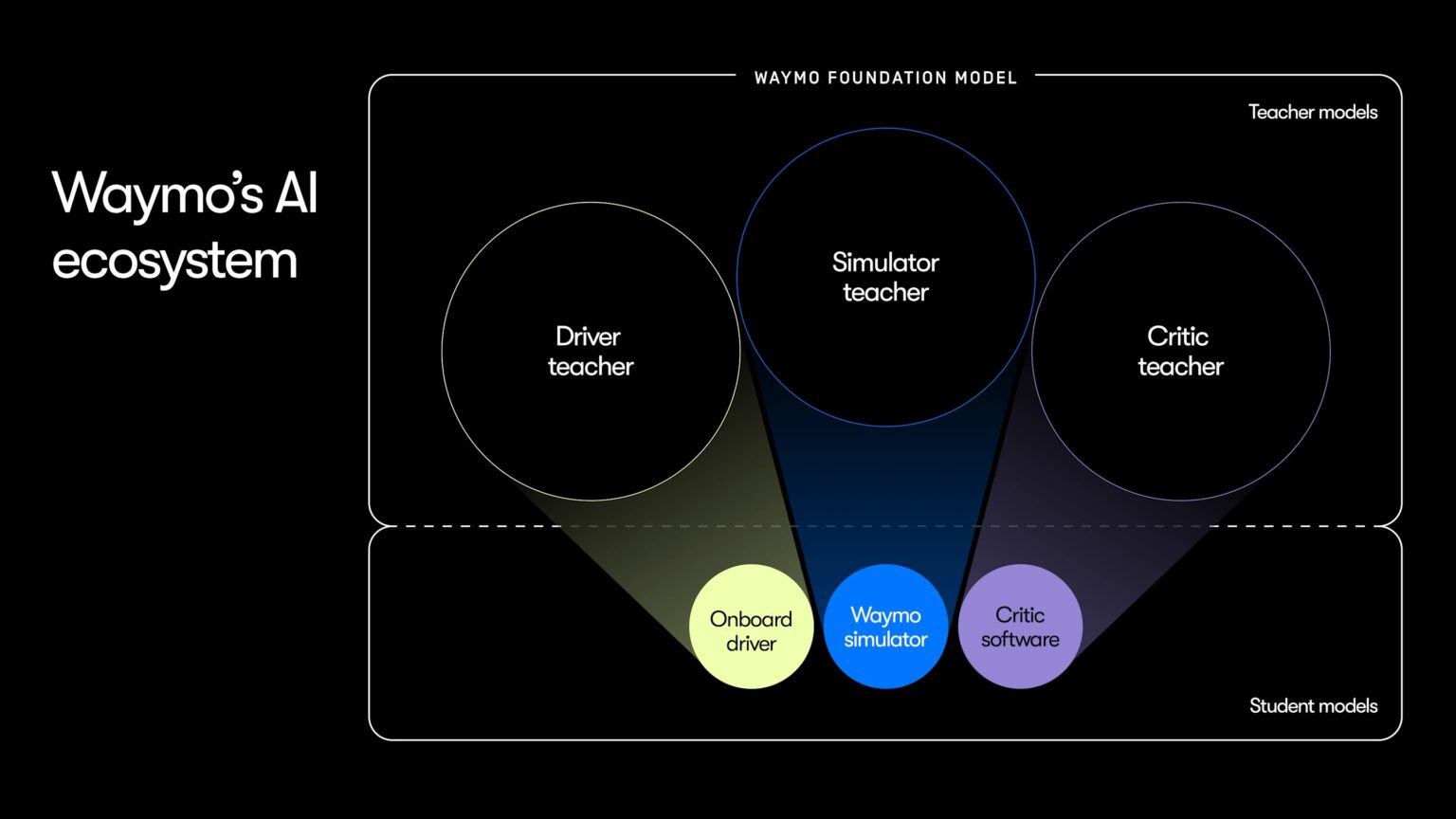

At the core of Waymo's system is a continuous feedback loop they call the Driver-Simulator-Critic architecture.

An AI model called the Critic automatically analyses every mile driven by the Waymo fleet, flagging suboptimal behaviour. Not just crashes or near-misses, but any driving behaviour that falls below the standard. This sensing function runs continuously, across every vehicle, every mile.

From those flags, improved driving behaviours are generated. These aren't deployed straight to vehicles. They're tested first in a sophisticated Simulator, across millions of scenarios, including edge cases that would take decades to encounter on real roads. The Critic then verifies the improvements in simulation. And only when Waymo's safety framework confirms the absence of unreasonable risk does the updated system get deployed to the real fleet.

Then the cycle begins again. New miles generate new data, the Critic finds new issues, improvements are generated, tested, verified, and deployed. The system gets better over time, not because someone scheduled an annual review, but because the architecture itself drives continuous improvement.

Write your awesome label here.

That is an adaptive governance mechanism. It has defined inputs (real-world driving data, every mile, every vehicle), concrete tools (the Critic model, the Simulator, the safety framework), and clear outputs (verified improvements, or a gate that prevents deployment until the standard is met). It runs continuously. It improves based on what it learns. And the governance process doesn't sit alongside the engineering. The two are inseparable.

It's not safety through a compliance checklist, nor through some arbitrary conformity assessment process.

Waymo didn't build a great autonomous driving system and then add a governance layer on top. The feedback loop that makes the driving better is the same feedback loop that makes it safe.

Just think about what this architecture makes possible that traditional governance approaches can't. The system doesn't rely on humans remembering to check something, or wait for an annual review cycle to surface problems, or depend on someone being brave enough to escalate a concern to leadership. Sensing is automatic. The improvement pathway is defined. The deployment gate is non-negotiable. Human judgment still matters enormously in the design of the safety framework, in defining what counts as unreasonable risk, in strategic decisions about where and how to expand operations. But routine detection of problems and verification of improvements doesn't depend on human vigilance alone.

Waymo also does something that most organisations in AI fail to do: they publish their safety methodology and make it reproducible. Their Safety Impact Hub compares crash rates against human benchmarks using publicly available NHTSA data, and they've published over twenty peer-reviewed safety papers. The methodology is open to scrutiny. That transparency isn't just good science. It's a governance choice, a decision to make your safety case verifiable by outsiders rather than asking people to trust your internal assessments.

Comparing the Waymo Way

So, let's compare the Waymo way to what happens when governance is designed with a more conventional mindset. I've written about several cases in previous editions of this newsletter, so I'll revisit some of them briefly here as they provide the instructive contrast.

Let's start with the collapse of Cruise, a former direct competitor to Waymo. Cruise had governance structures, safety documentation, processes on paper. But when their autonomous vehicle dragged a pedestrian in San Francisco in October 2023, the organisation's response revealed that none of it was real in the way that mattered. The subsequent Quinn Emanuel investigation, a 195-page external review, found what it called "poor leadership, mistakes in judgment, lack of coordination" and a "fundamental misapprehension of obligations." Over 100 employees knew about the dragging incident. Nobody disclosed it to regulators in the first interviews. Only media interviews brought it to the surface. The DOJ ultimately charged Cruise with providing false records to impede a federal investigation. The company paid $500,000 in criminal penalties and $1.5 million to NHTSA. Shortly after, as trust and confidence evaporated, the $30bn company collapsed. (Read my original article here)

They didn't lack governance. They lacked a culture that could carry governance through a crisis. People minimised instead of escalating. They managed the narrative instead of telling the truth. The mechanisms existed on paper but the organisational culture actively undermined them when it mattered most.

HireVue deployed AI-driven video interview assessments that analysed candidates' facial expressions to predict job performance. They had governance structures too: ethical principles, an advisory board, an independent audit by ORCAA, an AI explainability statement. But the science underneath was moving. Barrett et al.'s landmark 2019 meta-analysis on affect recognition (five scientists, over a thousand studies) concluded there was no reliable scientific basis for inferring emotion from facial movements. The AI Now Institute recommended banning affect recognition in high-stakes decisions. EPIC filed a formal complaint with the FTC. HireVue ignored the mounting evidence for years. They had assessed once and assumed they could continue using facial affect recognition, even while the science, regulation, and public scrutiny moved on around them. They eventually dropped facial analysis in January 2021, but only after sustained external pressure, not because their own governance detected the problem. (Expanded article here)

South Wales Police deployed automated facial recognition technology from a third-party supplier without conducting an adequate data protection impact assessment or equality impact assessment. The Court of Appeal found the deployment unlawful on three distinct grounds: too much discretion afforded to individual officers, an inadequate DPIA, and a failure to meet the Public Sector Equality Duty. It was the first successful legal challenge to automated facial recognition anywhere in the world. Much of the risk actually came via their suppliers, and an overconfidence in their claims. The police force had followed a deployer's playbook, they had done a normal level of vendor due diligence, but they couldn't see the full extent of AI-related risks flowing through their supply chain. (Expanded article here)

Three organisations who all had governance on paper. All failed. And not because they were negligent or malicious, but because their governance was designed for a snapshot, a point-in-time assessment that couldn't adapt when circumstances changed and wasn't supported by an embedded safety culture.

Static Governance vs. Adaptive Governance

For me, what stands out as the differentiator that separates Waymo from these failure cases isn't the presence or absence of governance. It's certainly not the strictness of regulatory compliance obligations. It's that in each of those cases, their approach to governance was static.

HireVue's governance was sincere, at least at first. But they assessed once, assumed that assessment held, and were either unaware or disregarded the mounting evidence against their practices. Cruise's governance existed on paper but the culture couldn't sustain it under pressure. South Wales Police's governance was procedural but incomplete, following a deployer's checklist without interrogating what was actually flowing through the supply chain.

Waymo's governance is adaptive. It senses change through continuous monitoring. It detects problems through automated analysis, not annual reviews. It responds through a defined improvement cycle with clear gates. And it improves its own controls over time as the system encounters new scenarios and the Critic learns what to flag.

I believe that the underlying reality that makes adaptive governance necessary is the same at every scale and in every context. This isn't just for the largest corporations and the most sophisticated autonomous systems. Models drift as data distributions shift. Humans adapt to AI tools in ways nobody anticipated, often through overreliance and complacency. The operating environment changes. Regulations evolve, attackers get smarter, the data itself shifts because your system is deployed and influences the world in which it exists.

Conventional point-in-time governance (assess, document, certify, move on) cannot keep pace with any of that.

What you need is governance that senses change, detects emerging harm, responds quickly, and improves its own controls over time. Governance that is designed deliberately, built on closed-loop mechanisms, and embedded in organisational culture.

I call that adaptive governance.

This is not just technical

I'm conscious that when you hear "adaptive governance" alongside words like "feedback loops" and "engineering," it's natural to think this is a technical approach for technical people. But it isn't, or rather it isn't only for technical people.

Adaptive governance is just as much about how laws and regulations are designed. How regulatory intent translates into organisational policy, and how policy translates into actual behaviour. It's also about how leadership culture is formed, how incentives shape decisions, how information flows through an organisation, and whether people feel safe raising concerns when something doesn't look right.

Look at the three cases again. HireVue failed on scientific due diligence and regulatory anticipation, not on technology. The Cruise disaster was a leadership culture problem: an organisation that couldn't tell the truth under pressure. And South Wales Police had a legal and procedural gap in how they assessed and documented the risks of a tool they bought from someone else.

Every one of those failures happened in the space between technology and governance. In the policy decisions, the leadership choices, the legal interpretations, the organisational behaviours. That's where adaptive governance lives. If you're a lawyer, a policymaker, a risk professional, a compliance lead, adaptive governance is just as much for you as as it is for an engineer. I'd argue it probably even matters more for you, because you're setting the conditions and constraints that determine whether good engineering actually translates into safe outcomes.

Seven Principles of Adaptive Governance

I've been applying adaptive governance throughout my career, though I rarely called it that. Over the past few months though, as I've taught more and more students through the Practitioner Program, I've had to step back and name it. To define the principles. To make explicit what was previously instinct refined by experience. I approach governance with one foot in engineering and one foot in regulatory understanding, and I needed to articulate why that combination produces results. I sometimes see others do likewise, building the bridge between governance and engineering with similarly positive outcomes, and I aim to help more practitioners do that. Because it works, and it's important.

The adaptive governance approach I apply and that I teach draws on multiple traditions. I've found that the term "adaptive governance" itself originates in the environmental commons literature, most notably Dietz, Ostrom and Stern's 2003 paper in Science, "The Struggle to Govern the Commons," which argued that governing complex shared systems requires institutional arrangements that can learn and adapt rather than rigid rule-based regimes. John Holland's work on complex adaptive systems provides the theoretical underpinning of how it is that AI systems exhibit the same properties as other complex adaptive systems, including emergent behaviour, feedback sensitivity, and non-linear responses to intervention. The approach also builds on the science of safety and the proven cultural practices of high-stakes industries: safety science, organisational learning, research into high-reliability organisations. But it draws equally on regulatory design, corporate governance, and what we know about leadership, organisational culture, and institutional behaviour under pressure.

I beleive there are seven principles or concepts that provide the essential foundations of adaptive governance:

Design-First. Nancy Leveson's Engineering a Safer World makes a powerful case that safety is an emergent property of a system, not something you can bolt on after the fact or locate in a single component. Governance works the same way. I previously wrote about the need to apply the lessons of safety design to AI (Article). It must be deliberately designed, not discovered by accident through accumulated policies and good intentions. There's an important distinction between scaffolding and building. Regulations and standards create scaffolding: they set expectations, they force questions to be asked. But scaffolding isn't the building. The actual safety comes from concrete design choices. How does information flow to people who can act on it? How can humans intervene when things go wrong? What happens when assumptions break? Waymo's Driver-Simulator-Critic system is governance designed in. HireVue's ethical principles were scaffolding with very little built inside.

Mechanisms. Jeff Bezos put it simply: "Good intentions never work, you need good mechanisms to make anything happen." A mechanism is a closed-loop system with defined inputs, concrete tools, clear ownership, measurable adoption, inspection, and continuous improvement (Article). Donella Meadows' Thinking in Systems explains why this matters: the behaviour of any complex system is determined by its feedback structure, not by the intentions of the people within it. A policy says teams should test for bias. A mechanism makes bias testing a mandatory gate in the deployment pipeline, so the code won't ship until the tests pass and the results are logged. When a new form of bias is discovered in production, it feeds back into the test suite, which gets stronger over time. The policy states an intention. The mechanism builds the behaviour into how work actually gets done.

Safety Culture. Without a culture of learning, psychological safety, and just accountability, mechanisms decay into ritual. Amy Edmondson's research on psychological safety, detailed in The Fearless Organization, demonstrates that teams where people feel safe raising concerns consistently outperform teams where they don't, particularly in high-stakes environments. Sidney Dekker's Just Culture provides the accountability framework: honest errors should trigger learning, not blame, but deliberate recklessness warrants sanction (Article). The distinction matters because people will only report problems if they trust the system to treat them fairly. Cruise is the cautionary tale. They had governance structures, but the culture wouldn't carry them through a crisis. People minimised instead of escalating. They spun instead of telling the truth. Culture isn't separate from governance. It's the foundation everything else sits on.

The Balcony and The Dance Floor. This concept comes from Heifetz, Grashow and Linsky's The Practice of Adaptive Leadership. You need the strategic view from above (the balcony), seeing patterns, interdependencies, and systemic risks across your portfolio. And you need the operational view from within (the dance floor), understanding how governance works in practice, where it helps and where it creates friction. The skill is moving between both. Leaders who stay on the balcony become disconnected from reality. Practitioners who never leave the dance floor can't see emerging patterns.

Vertical Connectivity. Weick and Sutcliffe's research on high-reliability organisations in Managing the Unexpected identifies "reluctance to simplify" and "sensitivity to operations" as two of the five principles that distinguish organisations that perform reliably under pressure. Both depend on signals flowing rapidly upward from operations to leadership, and intent flowing clearly downward. When bad news gets softened at every layer, when leadership's priorities don't reach the people doing the work, governance fails. (Article) Cruise is the cautionary tale here too, but so is any organisation where the risk register tells a different story from what's actually happening in production.

Technical and Adaptive. This distinction is central to Ronald Heifetz's Leadership Without Easy Answers. Technical problems have known solutions that experts can implement. Adaptive challenges require people to learn new ways of working, shift their assumptions, and change behaviour. Some governance challenges are technical: engineering controls, automated guardrails, monitoring systems. Others are adaptive: they require changes in how people think and act. The skill is diagnosing which you're facing. If you've tried solving a problem multiple times with technical interventions and it keeps recurring, you're probably facing an adaptive challenge, a cultural or behavioural issue that no tool will fix. Getting the diagnosis wrong wastes effort and breeds cynicism.

Approachable. Peter Senge's The Fifth Discipline makes the case that organisational learning depends on shared mental models and systems thinking being distributed across the organisation, not concentrated in a specialist function. I think the samehas to apply to governance. If only specialists can work with your governance, it doesn't work. The risks that matter most often emerge far from the central governance function: in development teams making architecture decisions, in operators noticing unusual system behaviour, in business units deploying AI into new contexts. Governance has to be expressed in language people understand and integrated into workflows they already follow.

Learning Adaptive Governance in Practice

I don't see these seven principles as abstractions. As I reflect on the 50+ articles I've written and shared over the past year, I see these same threads reappearing over and over again. They're the underpinnings of how I teach in the AI Governance Practitioner Program, and they shape every module, every case study, every exercise I put in front of students. Now, more explicitly.

In the program, you don't study adaptive governance as theory. You apply it. You design governance mechanisms for real scenarios. You diagnose whether a challenge is technical or adaptive. You practise moving between the balcony and the dance floor on case studies drawn from actual incidents. You build the muscle of thinking in feedback loops rather than checklists, because that's what the work actually demands.

The six weeks I spent articulating these foundations have changed how I see the program evolving. The first track and our AIGP exam preparation course is live and hundreds of practitioners are working through it, but I can see now where the curriculum needs to go deeper. More on how to think in systems, and what that means for how you design AI risk assessments. More on how to translate the variety of regulatory requirements, standards and frameworks to cohesive, coherent and unified controls. More on the leadership and culture work, and how to build accountability structures that people actually trust. More on the adaptive leadership skills that Heifetz describes, because so much of AI governance comes down to getting people to change how they work, and that's a leadership problem, not a compliance problem.

I also know that each of these seven principles deserves a full article of its own. So my next articles, and perhaps my whole year of articles will do exactly that: starting by taking one principle at a time, unpacking the science and real-world evidence behind it, and show how it applies in practice with real examples. If you've read this far and want to go deeper, that's what's coming.

And if you'd like to go even deeper, then I hope you'll join our program.

You know, most AI governance training starts with a framework or a regulation and teaches you to conform. My training is different. I start with the foundations of governance that actually work, the mindset and approach. Then I bring frameworks and regulations in as inputs. When governance is designed right, compliance becomes a byproduct of doing governance well, not the purpose of doing it. Waymo doesn't have a safety program because a regulator required it. They don't have ISO42001 certification, they don't implement the NIST Risk Management Framework. They have a safety program because they're putting two-ton autonomous vehicles on public roads and the work demands it. That's the relationship between governance and compliance I want to help every practitioner internalise. We do AI governance because it makes a difference for AI that is safe, secure and lawful.

If you want to see how this comes together, there is a free and open course that goes through these case studies and explains in more depth the adaptive governance approach. It'll also give you a clear sense of whether some parts or all of the Practitioner Program is the right next step for you.

Thank you for reading, and especially to all of you within our practitioner community. I hope this helps you understand the more explicit foundations of our practice and a clearer view of where we're going next.

References

1 Waymo (Dec 2025). "Demonstrably Safe AI For Autonomous Driving." waymo.com/blog/2025/12/demonstrably-safe-ai-for-autonomous-driving

2 Waymo Safety Impact Hub. waymo.com/safety/impact/

3 Kusano, K.D. et al. (2024). "Comparison of Waymo Rider-Only crash data to human benchmarks at 7.1 million miles." Traffic Injury Prevention, 25(sup1), S66–S77. tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15389588.2024.2380786

4 Di Lillo, L. et al. (2024). "Comparative safety performance of autonomous and human drivers." Heliyon, 10(14). sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2405844024104100

5 Di Lillo, L. et al. (2024). "Do Autonomous Vehicles Outperform Latest-Generation Human-Driven Vehicles? A Comparison to Waymo's Auto Liability Insurance Claims at 25.3M Miles." Waymo LLC.

6 "Comparison of Waymo Rider-Only crash rates by crash type to human benchmarks at 56.7 million miles." (2025). Traffic Injury Prevention. tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15389588.2025.2499887

7 Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan (Jan 2024). External Investigation Report re Cruise LLC. assets.ctfassets.net

8 R (Bridges) v Chief Constable of South Wales Police [2020] EWCA Civ 1058. judiciary.uk

9 Barrett, L.F. et al. (2019). "Emotional Expressions Reconsidered." Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 20(1). PMC

10 Dietz, T., Ostrom, E. & Stern, P.C. (2003). "The Struggle to Govern the Commons." Science, 302(5652), 1907–1912.

11 Heifetz, R.A. (1994). Leadership Without Easy Answers. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

12 Heifetz, R.A., Grashow, A. & Linsky, M. (2009). The Practice of Adaptive Leadership. Boston: Harvard Business Press.

13 Leveson, N.G. (2011). Engineering a Safer World: Systems Thinking Applied to Safety. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Open access

14 Meadows, D.H. (2008). Thinking in Systems: A Primer. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing.

15 Weick, K.E. & Sutcliffe, K.M. (2015). Managing the Unexpected: Sustained Performance in a Complex World (3rd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

16 Edmondson, A.C. (2019). The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and Growth. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

17 Dekker, S. (2017). Just Culture: Restoring Trust and Accountability in Your Organization (3rd ed.). Boca Raton: CRC Press.

18 Senge, P.M. (2006). The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization (rev. ed.). New York: Doubleday.

19 Holland, J.H. (2014). Complexity: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.