Jan 20

/

James Kavanagh

Creating your AI Governance Policy

How to create a straightforward, practical AI governance structure and policy that defines accountabilities and governance mechanisms. Most importantly, one that works.

First publication: 17th March 2025, Substantially revised 20th January 2026

I originally published this article in March 2025. What you're reading now is a substantial update that reflects nearly a year of working with clients, teaching, and building AI governance programs across different industries and organisation sizes. It incorporates everything I've learned while preparing and publishing the AI Career Pro course on Writing AI Governance Policies. Some of the advice has changed, some has sharpened, and quite a bit has been added based on what I've seen both work and fail in practice.

In previous articles on this blog, I've described a journey from developing the business case for AI governance to creating a comprehensive governance structure and set of mechanisms and controls that align with multiple regulatory frameworks and international standards. Now it's time to build the actual AI governance foundations for real in your organisation through formal policy.

This crucial step in operationalising AI governance starts with a well-crafted AI Governance Policy. This policy is not just an administrative document. Think of it as the constitutional framework that defines how your organisation will oversee, direct, and control its use of AI. Done well, it ensures that every AI initiative is developed, deployed, and monitored in ways that are safe, secure, and lawful, aligned with your organisation's values and risk appetite.

If your organisation already has a mature security or privacy management system in place, much of this will feel quite familiar. You'll recognise common elements like policy frameworks, governance committees, and escalation paths. The goal isn't to duplicate these structures but to thoughtfully extend them to address AI-specific considerations.

The Three-Policy Architecture

Before diving into the AI Governance Policy itself, it's worth understanding where it sits within a broader policy framework. In my experience, most AI policy confusion stems from organisations trying to solve three distinct problems with a single document: strategic oversight for leadership, risk management for development and operations, and practical guidance for employees. The result is often an unwieldy document that serves none of these audiences well.

The approach I recommend separates these concerns into three complementary policies that work together:

-

The AI Governance Policy provides strategic direction. It establishes principles, structures, and decision authorities. It's where you define who has accountability for AI governance and what your organisation's commitments actually mean in practice. This is your constitutional document.

-

The AI Risk Management Policy provides protective mechanisms. It specifies how you'll identify, assess, treat, and monitor the risks that AI systems create. It implements the risk management requirements that your Governance Policy mandates.

-

The AI Use Policy provides operational guidance for employees. When someone in marketing wants to use a generative AI tool to draft campaign copy, or an engineer pastes code into an AI assistant for debugging, this is the policy they need. It translates governance principles into practical guidance that anyone can understand and apply.

These three policies work together but remain distinct. The governance policy provides strategic direction. The risk policy provides protective mechanisms. The use policy provides operational guidance. When someone asks whether they can use a particular AI tool for a specific task, they look at the use policy. When a project team needs to assess whether their new AI system requires additional controls, they look at the risk policy. When a governance committee needs to make a decision about entering a new AI application domain, they look at the governance policy. Each document does its job without trying to do everything.

Now, it may well be the case that in a smaller organisation, especially one that is using but not building AI, these policies can be combined into one streamlined form. A thirty-person professional services firm doesn't need the same governance infrastructure as a multinational technology company. The principles don't change, but the packaging does. If that describes your situation, you might find that a single combined policy better fits your needs. I cover this streamlined approach in detail in the AI Career Pro course, but the foundational thinking in this article still applies.

You can learn how to write effective AI Governance policies with detailed walkthroughs of a Governance Charter, Governance Policy, Risk Management Policy, Use Policy, and even a streamlined AI Policy for small organisations. It's all within Course 4 of the AI Governance Practitioner Program

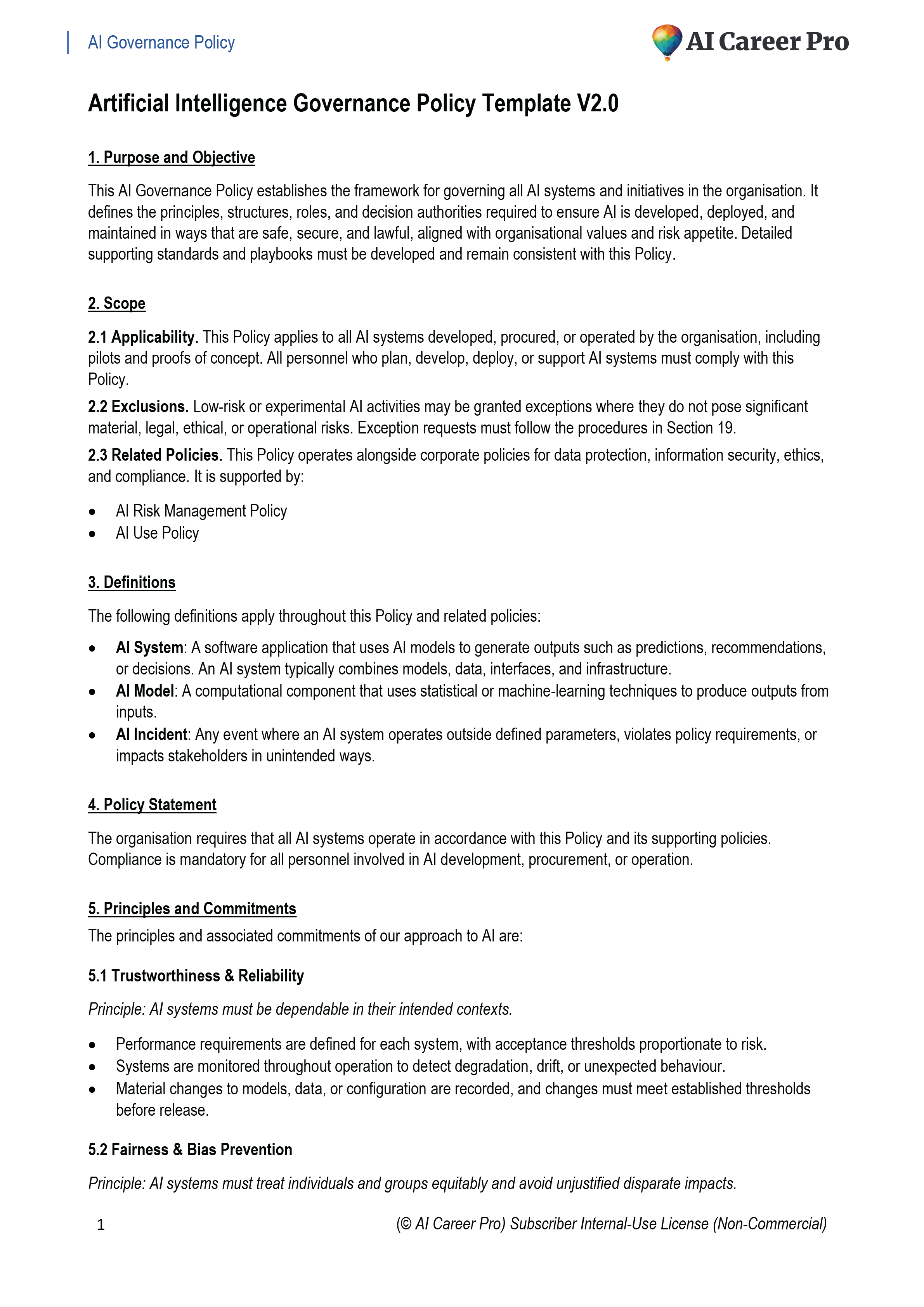

The first page of the AI Governance Policy template

Purpose, Principles and Commitments

The heart of your AI Governance Policy has to be a clear statement of purpose. Why are we governing AI, and what do we hope to achieve? This isn't about ticking regulatory boxes. It's about articulating a commitment to AI that is safe, secure, and lawful while still enabling your organisation to innovate and create value.

The purpose also needs to establish the relationship between this policy and other documents. Your governance policy tells you what must happen and who decides. Supporting documents like standards and playbooks tell you how to do it. By making this hierarchy explicit, you set the expectation that operational detail will evolve while core principles remain stable.

Scope comes next. Apply the policy to all AI systems: those you build internally, buy from vendors, or run as pilots. This comprehensive coverage prevents gaps where ungoverned AI might proliferate. Explicitly including pilots matters because organisations often treat experimental work as outside governance, and by the time a pilot becomes production, ungoverned habits have already formed. But scope also needs a release valve. Low-risk or experimental activities should be able to receive exceptions through a documented approval process. This flexibility prevents governance from stifling early-stage innovation.

With purpose and scope established, your policy needs to articulate guiding principles. This is where many policies go wrong. They either adopt generic principles copied from a framework without making them meaningful, or they produce lengthy philosophical statements that nobody can translate into action.

The challenge is that principles like fairness, transparency, and accountability are easy to agree with in the abstract. The struggle is describing them in ways that are clear, specific, and useful for actual decision-making.

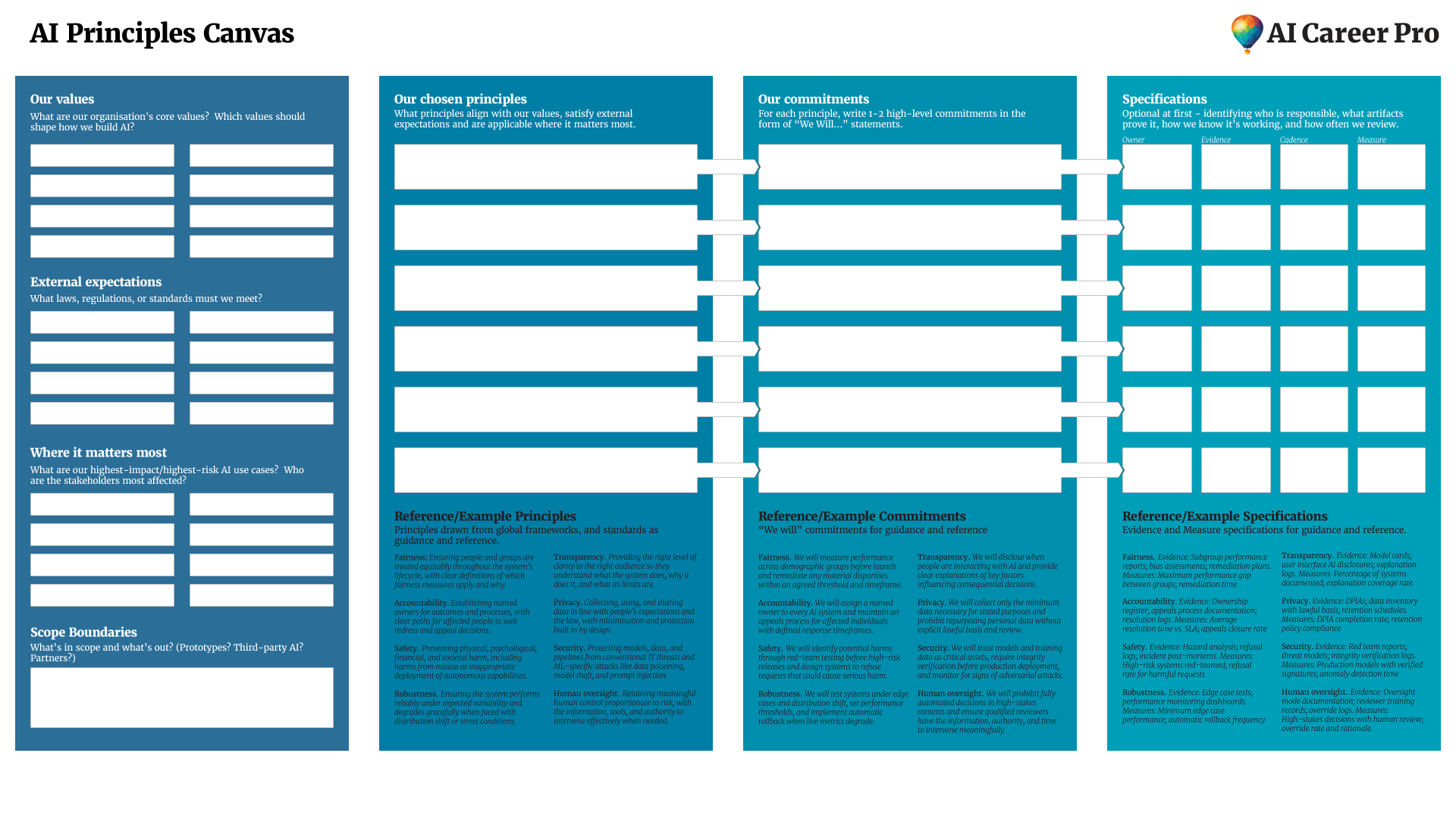

I've developed a methodology called the Principles Canvas that helps organisations work through this translation. I cover it in detail in Course 2, Organising for AI Governance, but the core idea is straightforward: move from values to principles to concrete "we will" commitments. Start with your organisation's existing values and mission. Look outward at regulatory expectations and recognised frameworks. Then prioritise ruthlessly, because you can't operationalise twenty principles. Choose a handful that matter most for your products, stakeholders, and risk profile.

The AI Career Pro Principles Canvas - a methodology for mapping values to principles, commitments and specifications.

Write each principle as a plain-language statement that a colleague can remember and act on. Then step from principle to commitment with specific "we will" statements. For fairness: "We will check for subgroup bias before launch and address material gaps." For transparency: "We will tell people when AI is used and explain key factors behind consequential decisions." For human oversight: "We will keep a qualified human in the loop for high-stakes outcomes."

These commitments should be actionable and measurable, even if you don't yet know exactly how they'll be implemented. As your program matures, you'll add the mechanics: who owns each commitment, what evidence it produces, how success is measured. You don't need all that detail on day one. What you need is enough clarity that teams understand the direction and can start making better decisions immediately.

You can learn how to turn organisational values and principles into specified commitments using the AI Career Pro Principles Canvas within Course 2, Module 7 of the Program.

Structure, Roles & Responsibilities

A well-designed governance structure creates clear pathways for decisions, oversight, and accountability without drowning your organisation in paperwork. The goal is ensuring signals flow efficiently to where decisions need to be made.

The approach I recommend uses a three-tier structure that matches decision authority to decision impact. At the top, an AI Governance Committee provides strategic oversight: major initiatives, risk thresholds, policy changes, and high-impact system approvals. This committee should be chaired by a senior executive, which signals that AI governance sits at the leadership level rather than being delegated to middle management.

Below that, an AI Operational Committee handles day-to-day governance activities. This is where most decisions actually happen. New systems, significant changes to existing systems, performance monitoring, operational risk management. The Operational Committee has delegated authority to approve most work, escalating to the Governance Committee only when issues exceed defined thresholds.

At the foundation, technical teams handle routine operational decisions within documented parameters. They monitor models, manage data, respond to minor incidents, and keep systems running. They don't need committee approval for every configuration change, but they do need to escalate when something falls outside normal parameters.

This separation solves two common failure modes. It stops executives from becoming bottlenecks for routine decisions. If every model update needs Governance Committee approval, you'll either grind to a halt or people will start bypassing the process entirely. At the same time, it ensures significant issues actually reach senior leadership rather than being buried in operational processes.

For smaller organisations, you might combine these functions. Perhaps your CTO chairs both committees, or the Operational Committee is simply a standing agenda item in an existing technical leadership meeting. The principle remains constant even as implementation scales: match decision authority to decision impact, and ensure every level has clear escalation paths to the next.

Defining Accountabilities

Rather than creating an entire governance bureaucracy, I always encourage extending existing roles to cover AI-specific requirements where it's possible. This takes advantage of organisational expertise while maintaining clear accountability. I say that with one exception in mind - I believe a dedicated role for an AI Governance Lead is essential in all large organisations.

Three roles are central to making governance work in practice: the AI Governance Lead, System Owners, and Mechanism Owners.

The AI Governance Lead is the linchpin of the entire framework. This person coordinates implementation across the organisation, maintains the policy framework, facilitates both committees, and serves as the central point of contact for governance matters. More importantly, they bridge strategic and operational levels. They participate in Governance Committee discussions about risk thresholds and policy direction, then work directly with technical teams to translate those decisions into practice. Without this bridging function, governance becomes disconnected. Executives set policies that don't reflect operational reality. Technical teams build systems that don't align with organisational intent.

System Owners embody a principle that runs throughout effective governance: single-threaded ownership. Every AI system must have a designated owner who is accountable for that system's compliance throughout its lifecycle. Not a committee. Not a shared responsibility. One person who can answer the question: "Who is responsible for this system?" When accountability is diffuse, problems fall through cracks. The data team assumes engineering is handling monitoring. Engineering assumes operations is managing incidents. With a System Owner, there's no ambiguity.

System Owners aren't governance specialists reviewing paperwork from a distance. They're typically the engineers or product managers who deeply understand the systems they oversee. This embeds governance into operational teams rather than imposing it from outside.

Mechanism Owners apply the same single-threaded ownership principle to governance infrastructure itself. A mechanism is any process, tool, or control that supports governance: your risk assessment process, your model validation procedure, your incident reporting system. Each of these needs an owner who ensures it actually works, maintains supporting documentation, and recommends improvements based on operational experience. Without this ownership, governance mechanisms decay. The risk assessment template that made sense two years ago becomes outdated. The approval workflow that worked for five systems becomes a bottleneck at fifty.

Let me be clear about what these ownership roles actually are. They're about allocating accountability, not creating new job titles. Only in the largest organisations will these be dedicated full-time positions. For most organisations, System Owner or Mechanism Owner is a role someone plays alongside their other responsibilities. An engineer might be the System Owner for one or two AI systems while still doing engineering work. The point is that someone specific is accountable, not that you need to hire a team of owners.

The remaining roles in your policy will likely include familiar positions: a sponsoring executive who chairs the Governance Committee, legal and compliance advisors, a data protection officer, internal audit, and technical staff. Each needs clear responsibilities defined, but these typically extend existing roles rather than creating new ones. The art is integration, not duplication.

Asserting the Mechanisms of Governance

If there's one area that has significantly changed in the writing of this article since March 2025, it's this: the central importance of adaptive mechanisms. My research, consulting and discussions since has just reinforced my appreciation that what separates governance that works from governance that fails is this: good intentions never work. Mechanisms do.

You need good mechanisms to make anything happen. That observation, often attributed to Jeff Bezos, captures something fundamental about how organisations actually operate. You can have ethical principles, advisory boards, transparency commitments, and accountability structures. But intentions don't automatically translate into consistent action, especially when teams face competing pressures.

Consider what happens when you publish a policy requiring teams to test their models for bias. The policy might even provide detailed instructions and metrics. But it still depends on teams remembering, caring, and executing correctly under pressure. Every deadline, every resource constraint, every competing priority creates an opportunity for the policy to be ignored or partially followed. Multiply this across dozens of teams and hundreds of decisions, and you see why policy-based governance so often fails to achieve its intended outcomes.

A mechanism operates differently. Instead of hoping teams do the right thing, a mechanism makes the right behaviour either automatic or mandatory. It takes defined inputs, transforms them through concrete tools and processes, and produces predictable outputs while continuously improving through feedback loops. Where a policy states intentions, a mechanism builds desired behaviours into the structure of work itself.

I teach this approach in detail in Course 3, Governance through the AI Lifecycle, drawing on lessons from organisations that have made mechanism-based thinking central to their operations. Let me outline the key components here.

You can learn how to design and specify adaptive governance mechanisms that span the lifecycle of AI Governance and take advantage of over 30 prepared Mechanism Care templates within Course 3 of the Program.

Every effective mechanism operates through six essential elements. First, defined inputs and outputs establish what the mechanism transforms. Inputs are controllable elements that flow in: risk assessments, deployment requests, model metadata. Outputs are tangible artifacts it produces: completed model cards, audit logs, deployment approvals. Critically, these outputs frequently become inputs to other mechanisms, creating an interconnected governance system.

Second, a tool sits at the heart of the mechanism, providing the concrete capability that transforms inputs into outputs. This isn't a suggestion or guideline but actual software, automated workflows, or systematic processes that make the desired behaviour either automatic or mandatory. For AI governance, this might be a model card generator integrated into your training pipeline, an automated bias testing framework that runs within CI/CD, or a risk assessment system that gates deployment decisions.

Third, ownership creates accountability through a single-threaded owner whose success depends on the mechanism's effectiveness. This person doesn't just oversee the mechanism; they define it, drive adoption, measure impact, and continuously improve it. Without clear ownership, mechanisms decay into abandoned processes that teams work around.

Fourth, adoption happens when the mechanism becomes embedded so deeply into workflows that using it is easier than avoiding it. The most effective adoption strategy is architectural: make the mechanism a required step in existing processes. Teams can't deploy without completed model cards. They can't access production data without privacy review. Code won't merge without passing fairness tests. When the mechanism blocks progress until satisfied, adoption shifts from optional to inevitable.

Fifth, inspection provides continuous visibility into both usage and effectiveness. This goes beyond periodic auditing to include real-time metrics on whether the mechanism is being used and whether it's achieving its goals. A documentation mechanism tracks not only whether model cards exist but whether they're complete, current, and actually consulted during incidents.

Sixth, continuous improvement distinguishes mechanisms from static processes. Every failure becomes a lesson, every workaround reveals a gap, every trending metric triggers adjustment. The mechanism includes its own evolution process: how feedback gets collected, how changes get prioritised, how improvements get deployed. This recursive quality enables mechanisms to strengthen over time rather than decay into bureaucracy.

The real power of mechanisms emerges when they connect into coherent systems. Individual mechanisms solve specific problems, but connected mechanisms create comprehensive governance that scales. When a team trains a model, the documentation mechanism automatically generates a model card. This model card becomes input to the inventory mechanism. The inventory mechanism uses risk scores to trigger audit mechanisms for high-impact systems. Audit findings feed into training mechanisms that update documentation templates. Each mechanism strengthens the others.

This interconnection solves the scale problem that defeats policy-based governance. Instead of requiring hundreds of engineers to understand and correctly apply dozens of policies, you embed requirements into the tools they already use. The bias testing framework runs automatically in their development pipeline. Privacy checks integrate into the data access layer. Governance becomes part of the development process rather than an additional burden imposed from outside.

Your AI Governance Policy asserts that these mechanisms must exist. It mandates that systems be registered, that risks be assessed, that incidents be reported and learned from. But the policy doesn't contain the mechanisms themselves. Those live in your standards and playbooks, owned by Mechanism Owners who continuously refine them based on operational experience. This separation keeps the policy stable while allowing the mechanisms to evolve rapidly as you learn what works.

Exceptions as Feedback

Every governance framework needs a formal exception process. No matter how carefully you design your policies, reality will present situations that don't fit neatly into your framework. A project with unusual characteristics. A business opportunity requiring faster movement than standard review allows. A legacy system that can't comply with new requirements without major rework. Without a formal exception process, teams will create their own workarounds outside your visibility.

A good exception process channels deviations through proper review rather than letting shadow practices develop. It requires documented justification including the business need, the specific requirements being waived, the risks of granting the exception, and any compensating controls. It routes requests through someone with appropriate authority. And critically, it tracks exceptions over time.

In my own experience, I’ve found that many organisations miss how valuable exception patterns are as policy feedback. If you're constantly approving exceptions for the same requirement, that's a signal. Either the requirement is poorly calibrated to actual risk, circumstances have changed since the policy was written, or there's a gap between policy assumptions and how work actually happens. Quarterly review of exception patterns often reveals more about governance effectiveness than compliance metrics. This reframes exceptions from governance failures to governance feedback. A well-functioning exception process indicates governance that's responsive to operational reality while maintaining appropriate oversight.

Integrating with Existing Functions

Most organisations can't dedicate multiple people solely to AI governance. Success comes from extending existing roles and integrating with existing processes. The risk analyst who handles security assessments adds AI risk evaluation to their toolkit. The data protection officer who oversees privacy expands their scope to include AI-specific considerations. The key is providing these professionals with focused training on AI-specific risks and appropriate support.

Cross-functional coordination emerges naturally with thoughtful role positioning. The AI Governance Lead regularly joins security reviews when AI systems are discussed. System Owners participate in risk assessments for their systems. Business leaders whose departments use AI join governance discussions affecting their operations. This organic collaboration often proves more effective than forced coordination mechanisms.

If you already have robust policies for data protection, risk management, or information security, don't create parallel AI-specific versions. Extend your existing frameworks to address AI-specific considerations. Your security policies likely already cover system access and monitoring; they just need enhancement to address AI-specific risks like prompt injection or model extraction. Your change management processes can be extended to handle AI-specific considerations like model retraining or data updates. This integration prevents the policy sprawl that often undermines governance efforts.

That said, some aspects of AI governance do demand dedicated attention. The three-policy architecture I described earlier reflects this reality. Your AI Governance Policy establishes the constitutional framework. Your AI Risk Management Policy addresses the unique ways AI systems create and amplify risk. Your AI Use Policy provides practical guidance that employees can actually follow. These work together as a coherent system, each serving different audiences and purposes.

Conclusion

The AI Governance Policy is not a static document. It's the constitutional framework that underpins every AI initiative within your organisation. By clearly defining purpose, establishing a scalable governance structure, delineating roles and responsibilities, and integrating robust oversight mechanisms, the policy lays a solid foundation for AI that is safe, secure, and lawful.

The three-policy architecture I've described separates concerns appropriately: strategic oversight in the Governance Policy, protective mechanisms in the Risk Management Policy, and practical guidance in the Use Policy. Each document serves different audiences and purposes while working together as a coherent system. For smaller organisations, these can be combined into a streamlined single policy, but the underlying principles remain the same.

In the AI Career Pro course on Writing AI Governance Policies, I walk through complete templates for all three policies section by section, explaining the reasoning behind each component and how to adapt them to your specific context. The course includes downloadable templates, the Principles Canvas for developing your commitments, and detailed guidance on everything from governance structures to exception processes.

Thank you for reading. Please do subscribe and as always, I really welcome any feedback or suggestions.

Copyright © 2026

Australian-founded, serving professionals worldwide.